Gabriela Vaz Meirelles, The Day and the Night, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 100 cm, 2023

Day, Night and Philosophy

Day, night and philosophy are linked by a close relationship. This is suggested in the name of this particular type of knowledge. Philosophy (in ancient Greek: φιλοσοφία, philosophia) is in fact composed of philos (φίλος), which means 'love', and sophia (σοφία), which means 'wisdom' and refers to phos (light). Therefore, philosophy ultimately means 'love of wisdom' or 'love of the light that reveals'. Or, more boldly, we could say 'love of the day'. If we think of the night as that place and that time in which the light is absent, the sun hides and men retreat, the night is par excellence the counterpoint to philosophy.

Philosophy illuminates and delays the night, which is usually seen as a negative pole. In the renowned Allegory of the Cave, Plato imagines the progressive ascension to knowledge starting from the realm of non-knowledge. Those who find themselves bound to contemplate exclusively the things of this world live in a sort of cave that prevents the light of the sun from illuminating the interior. Their existence is that of a perpetual night, where shadow, illusion and appearance reigns. Only the philosopher, connoisseur of light, can save them by descending back to the dark and rescuing them, but at the cost of his life.

Theogony as Inspiration

The work “The Day and the Night” takes inspiration from Hesiod's Theogony. It dates back to 700 BC and shows us the path that leads from the initial Chaos to when Zeus becomes king of the gods, establishing a relative cosmic order among the Olympian gods. Cosmos in fact means "order". Chaos is a Greek word of neutral gender, the personification of a divinity, whose meaning is Abyss, Chasm, Void.

In the preface to the Theogony, the nocturnal and invisible procession of the Muses makes the gods of the "current" cosmic phase and of the two "previous" phases appear in their voices (v. 11-21), as if there were an "ascending" theogony, to go back from the "current" gods, Zeus, Hera, Apollo, to the divinities of the "previous" generations, also to the original forces from which they all came to light: "the Earth, the great Ocean, the black Night". It then ends with the black Night (expression of non-being, the daughter of Chaos, the surrounding and solitary night generating all the forces that mark man's life with deprivation) and the reference to the sacred generation (= being) of the other immortals.

In this archaic wisdom, which found its clearest (and darkest) expression in Heraclitus, every opposite, when it appears in the light of existence, brings with it, by determination of its essence, also its opposite. This tension produced by the acute vision of the unity of opposites penetrates and permeates the entire Theogony – and the entire Greek Myth and Religion.

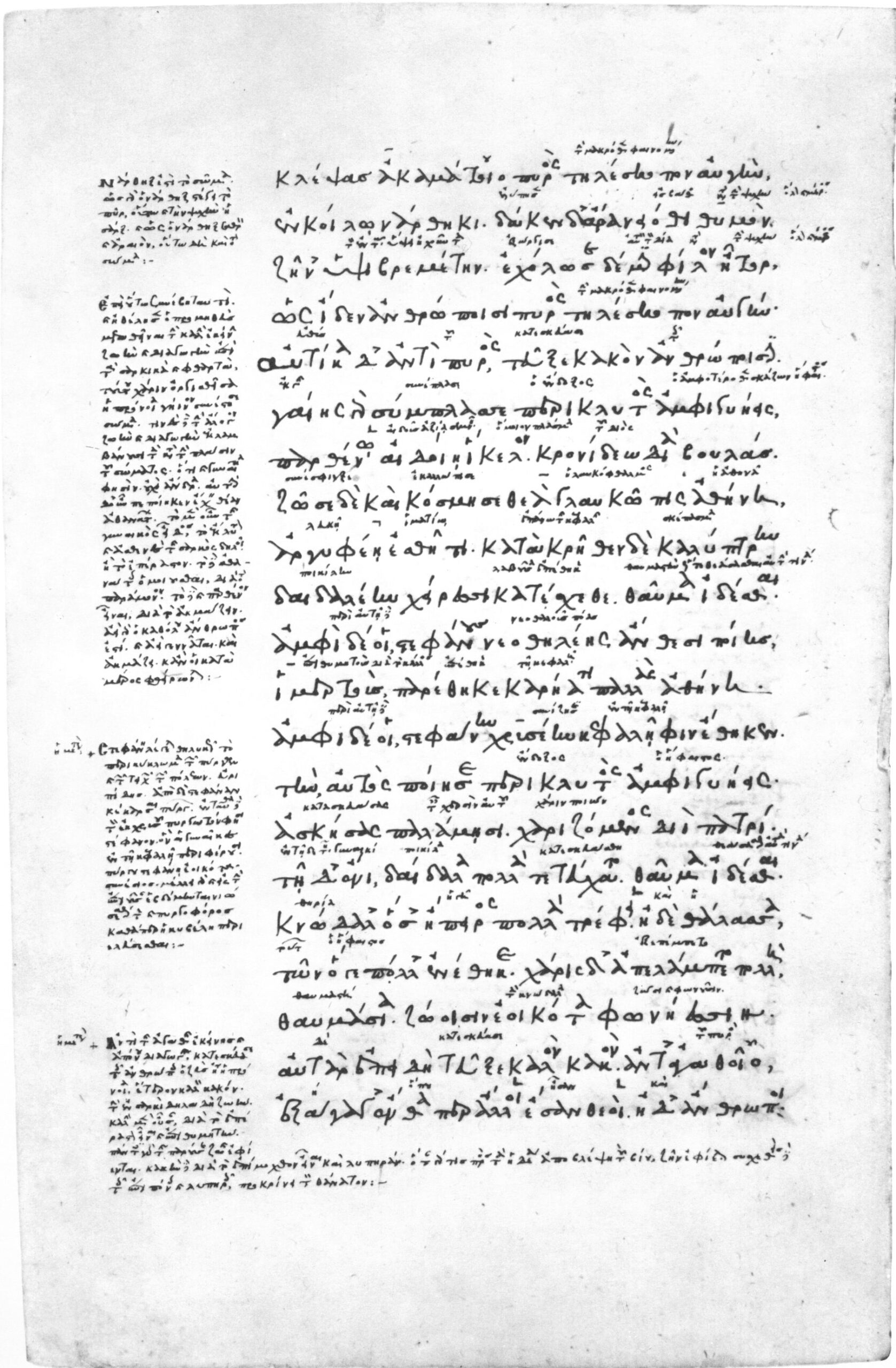

Fourteenth-century Greek manuscript of Hesiod's Theogony

According to Greek mythology, in the beginning, the first to be generated was Chaos, or an abyssal void without order. This disorder is represented by a divinity capable of generating. There are two forms of procreation in Theogony: by loving union and by cissiparity. The first beings are all born through cissiparity: an original divinity splits, remaining itself, at the same moment in which another divinity emerges from it through schizogenesis. Thus from Chaos were born Erebus and Night (v. 123).

“In truth at first Chaos came to be, but next wide-bosomed Earth, the ever-sure foundation of all the deathless ones who hold the peaks of snowy Olympus, and dim Tartarus in the depth of the wide-pathed Earth, and Eros (Love), fairest among the deathless gods, who unnerves the limbs and overcomes the mind and wise counsels of all gods and all men within them. From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night; but of Night were born Aether and Day, whom she conceived and bore from union in love with Erebus.”Hesiod, Theogony, 116-125

All descendants of Chaos belongs to the sphere of non-being; all of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren (except Aether and Day) are dark powers, they are forces that deny life and order. His children are Erebus and Night. Erebus is a sort of antechamber to Tartarus and the kingdom of what is dead. Night, after having given birth to Aether and Day, united with Erebus in love, generates through cissiparity the forces of debilitation, penury, pain, oblivion, weakening, annihilation, disorder, torment, deception, disappearance and death: in short, everything that has the sign of non-being. Night and her children (v. 211-213) express it metaphysically as the principle of destruction and loss which in various forms acts dramatically in human life.

“And Night bore hateful Doom and black Fate and Death, and she bore Sleep and the tribe of Dreams.”Hesiod, Theogony, 211-213

These negative powers, the entire lineage of Chaos, are generated by cissiparity; Aether and Day are exceptions because they are the only positive and luminous powers within this lineage, generated by a union of love. In this way light comes out of the darkness, from the initial Chaos (disorder) the Cosmos (order) began to emerge. In this case, there is a mirror symmetry between the parents and the generated children: Erebus is the underground, the dark and nocturnal region linked to the kingdom of the dead, a kind of bottomless abyss; Aether is the upper region of splendid brightness in the daytime sky. Thus Erebus, the infernal darkness, has only the same inverted position and nature as Aether, the celestial brightness. This is also true between Day and Night, which are ontological principles that visually express the sphere of being and non-being, and have an intimate and profound relationship between them.

The verses (v. 744-757) tell us that every evening, Night came from the east, carrying her son Sleep on her arms, to cover the sky and obscure the shining blue of the celestial vault (Aether), but every morning Day dispersed the mists of the mother to cover the earth again with the light of Aether. In ancient cosmogonies, Night and Day were real substances distinct from each other and independent of the Sun since it dominated the day but its light was not its source.

“There stands the awful home of murky Night wrapped in dark clouds. In front of it the son of Iapetus stands immovably upholding the wide heaven upon his head and unwearying hands, where Night and Day draw near and greet one another as they pass the great threshold of bronze: and while the one is about to go down into the house, the other comes out at the door. And the house never holds them both within; but always one is without the house passing over the earth, while the other stays at home and waits until the time for her journeying comes; and the one holds all-seeing light for them on earth, but the other holds in her arms Sleep the brother of Death, even evil Night, wrapped in a vaporous cloud.”Hesiod, Theogony, 744-757

Etymology and Symbolic Projections in Greek and Christian Culture

Birth and death alternate in man's existence just as day and night are part of our life, time and mark us irreversibly. The experience of day and night is shared by all the religions and appears in ancient mythologies and cosmogonies, in Judaism and Christianity.

In Greek mythology, the day is represented by a primordial deity, Emera (in ancient Greek: Ἠμἐρα, Hêméra). On the other side, the Greek term that designates the night, Nyx (in ancient Greek: Nύξ, Nýx), from which the Latin nox-ctis, whose root is at the origin of the designations of night in modern languages (English: night; German: nacht; French: nuit; Spanish: noche; Portuguese: noite) primarily indicates the night as a time without sunlight. The concept extends to other similar terms, in the true sense, darkness (Ps 104:20), and in the translated sense, blindness, death, abandonment, evil (Jn 9:2). The ambivalence of its meaning is observable from the beginning. In fact, among the Greeks it is considered a reality of terror and insecurity, but also a friendly reality, which provides the restful sleep necessary for the entire cosmos. It forms a pair with the day, symbolically contrasting itself with it. Nyx corresponds mythologically to a deified figure, generally an anthropomorphism linked to magical and nocturnal rites, which makes use of the power of darkness and the stars and easily reveals itself in dreams or visions. Nonetheless, the night represents a privileged time of revelation, in which the divinity, with the favor of silence and darkness, carries out a project, self-revealing itself to man and his conscience, calling to discern the signs of a mysterious itinerary, not possible for man in his daily toil.

In Christian culture, the night, a beautiful creature of God, was desired from the beginning; the day would not be understood without the night (Gn 1:3-5). The understanding that God's work happens mysteriously in the night and brings the light of novelty means reviving the Christian experience as an event of salvation and exultation.

For the Israelite, the night (in Hebrew: laylàh) is an event full of memories, promises, hopes. At least three components form the Old Testament core of the meaning of the night: creation (bara'), passage (pesah) and prayer ('tr). All creation is immersed in the night until God calls it to light. At sunset, the night recalls the work of creation, the powerful spirit of God who, in the sleep of life, forms the cosmos. Creation expresses all its desire for liberation and completeness. However, in the night, while the human race languishes because of the evil committed, so that the night reminds us of death, the abysmal void of the cosmos with its fears, God speaks and promises a new creation: to Noah (Gn 8:22), to Abraham (Gn 15:17), to Isaac (Gn 26:24), to Jacob (Gn 46:2), to the ones called to guide the people on their journey of freedom (2 Chro 7:12). The night of the liberation from the slavery of Egypt, the passage, is therefore central, since God carries out the plan of liberation in the middle of the night (Ex 11:4; Ex 12:12; Ex 12:29). Besides, as a space for abandoning one's heart to the most hidden feelings, the night also becomes a time for prayer and invocation. The psalmist rises "at midnight" to give thanks to God for his righteous judgments (Ps 119:62); like a sentinel, fidelity to Yahweh and the desire to celebrate it during the nights are confirmed (Ps 42:2; Is 26:9), since the soul yearns for God (Ps 130:6) and burns with the desire to meet and contemplate Him (Is 21:11-12; Ps 134).

Finally, the Easter night marks the passage between the expectation and the fulfillment of salvation. Starting from the Easter night we understand the meaning of the night in the life of Jesus and the Church, fulfillment of the Father's salvific plan. The ambivalence of the night also appears in the earthly life of Jesus: on the one hand it represents the space of encounter with the Father (adoration-entrustment-prayer-election), on the other it symbolizes the danger of the kingdom of darkness (solitude-poverty-trial-temptation); joy and suffering, exaltation and tears, certainty and doubt, hope and anguish coexist in the nights of Jesus. From the beginning to the end of his earthly existence, Jesus entered in the night: the shepherds receive his joyful announcement (Lk 2:8-20), and the wise men, who have come from afar, contemplate him "shining" in the night ( Mt 2:9-12). Then reaches the nocturnal loneliness in the death and burial of Christ. It is the night of the "descent into hell", into the bowels of the earth to bring light to those who walked in darkness and waited in hope. But "at nightfall" (Mt 28:1) the mystery of life is fulfilled, the triumph of light over darkness: the Easter of the Lord, announced by the angels as the definitive liberation. With the resurrection of Christ the night becomes bright and fruitful (Jn 21:3-14), the tomb remains empty forever, the guardians stunned, the amazed disciples share bread and joy (Lk 24:13-35).

Whoever lives in the new reality gives a paschal meaning to everything that surrounds him as a "child of the day" (1 Thes 5:5; Eph 5:8) since, by virtue of the passage through the darkness of the world and its culture of death he is been "freed from the power of darkness", from "dark thoughts" (Eph 4:18) and from "dead works" (1 John 2:8; Rm 13:12). The Church contemplates Christ the bridegroom during the night and watches over his return (Lk 17:34; Mt 25:6), uniting in the cosmic praise of the celestial elders, day and night (Rev 4:8) and of the saints (Rev 7:15), active in charity (1 Thes 2:9; 2 Thes 3:8) waiting to dwell in the heavenly Jerusalem with the everlasting light of the Lamb (Rev 21:25; Rev 22:5).

The night therefore represents the necessary "dialogue" with the day and marks the passage of time. The night becomes at the same time an experience of blindness and a condition of liberation, a privileged place for a journey of research and self-discovery, of the capacity for liberation and openness towards others and towards God. The night implies the practice of the virtue of hope, a "nocturnal virtue", an exercise in waiting that involves God and man through a profound search for love. The entire human journey is wrapped in the dialectic between light and night and at the same time marked by hope. Night and hope almost merge and become companions in our struggle to live and love.

“Love worketh no ill to his neighbour: therefore love is the fulfilling of the law. And that, knowing the time, that now it is high time to awake out of sleep: for now is our salvation nearer than when we believed. The night is far spent, the day is at hand: let us therefore cast off the works of darkness, and let us put on the armour of light.”Rm 13:10-12

The Composition

In mid-2023, Gabriela was commissioned to paint a mythological mural on the ceiling of a room of approximately 20 m2 in an apartment in Florence. Since the ceiling was divided into two sections, the artist proposed the theme of day and night. She was very happy with the opportunity to represent this important subject of ancient cosmogony and tof he life experience of all men, in different cultures, through a large-scale painting. For the realization of the composition, Gabriela took inspiration from Hesiod's Theogony, particularly based on the verses that describe the moment when, every evening, the goddess Night (Nyx) came from east to west, carrying her son Sleep, to cover and darken the shining blue of the celestial vault (Aether) but, every morning, Day returned to replace her, greeting her and dispersing his mother's mists to cover the earth again with the light of Aether. Although the Day is represented in Greek mythology by a primordial female deity, Hemera, the artist decided to depict it as a male figure, referring to the Italian noun gender. Gabriela then developed the composition in two sections, each divided into three parts: a central roundel and two lateral polygons. For the first section, at the entrance to the room, the composition of the day was proposed and for the other section behind, that of the night.

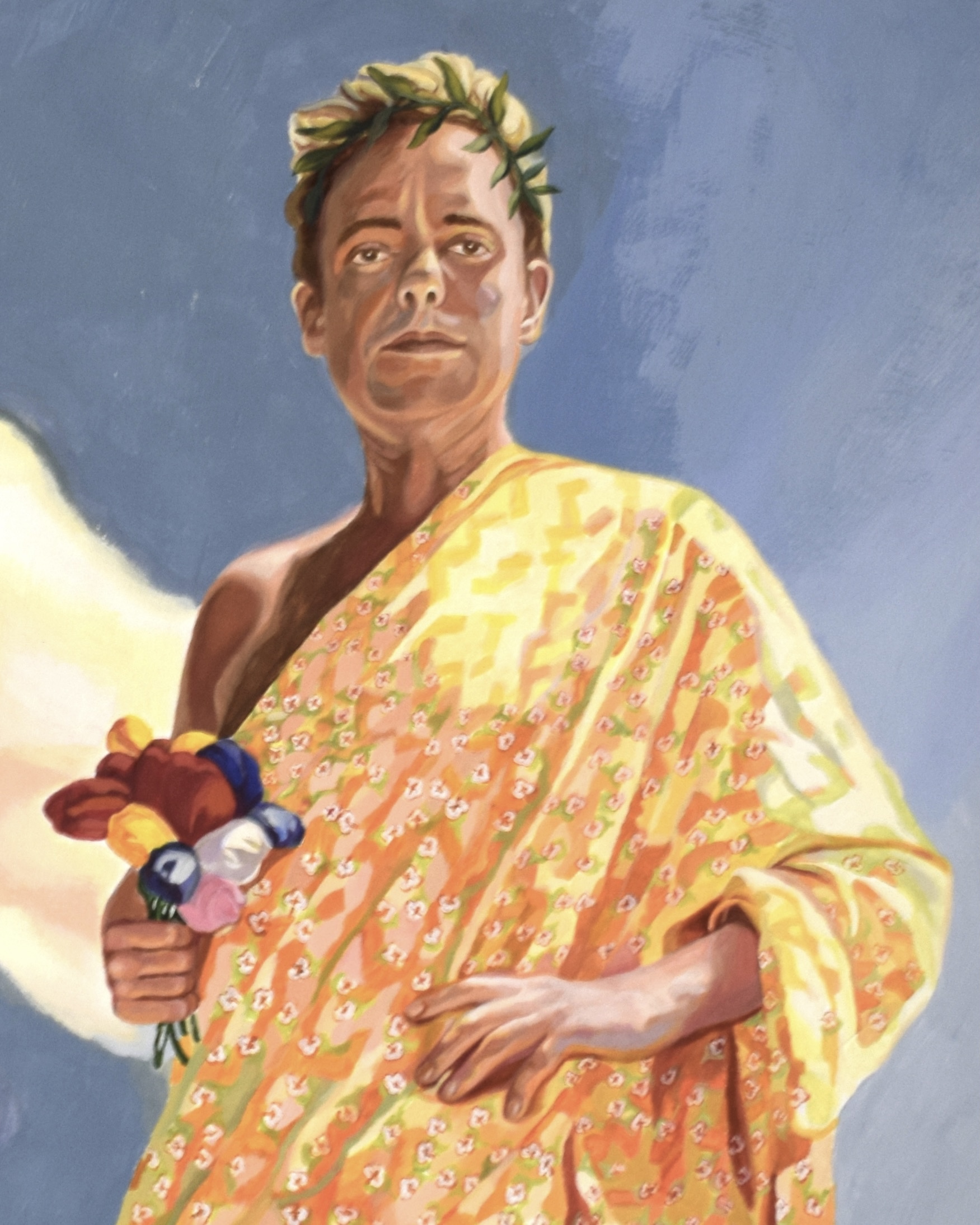

The Day, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 cm, 2023

In the Day roundel, the personification of Day is depicted standing on white clouds against a background of radiant blue sky, wearing a yellow flowered dress and carrying a bouquet of colorful flowers that reminds us of spring. A laurel wreath, which in Greco-Roman mythology symbolized wisdom and glory, encircles the forehead of the Day. Laurel was considered a sacred plant in classical culture: it was associated in particular with Apollo, god of the sun and wisdom, music, poetry, sculpture and painting. The bare feet rest on the clouds, in a reference to the celestial and spiritual dimension. To the right of the Day, above, a white dove is depicted carrying an olive branch, a symbol of peace and reconciliation and an expression of divine will in Christian culture. It recalls the story of the universal flood, when after the rain, Noah sent out a dove to explore which returned with an olive branch, a sign of God's forgiveness towards men.

In the lateral polygons of the Day roundel, the same dove of peace is represented surrounded by the sun and white clouds and, on the left, a shower of colorful spring flowers of different species are shown, including the olive tree, the rose and the daisies. The latter, since ancient times, have been linked to purity and nobility of soul. It is a flower with its pure white petals and its yellow center that recalls the sun, innocence and positivity. The red rose, in turn, is the queen of flowers and has always symbolized love. In Christian culture, roses have always accompanied, in the figurative arts, the figure of Mary, sometimes represented in a rose garden, or with a rose in her hand, or referring to the rosary, overwhelmed by a cascade of roses. The Virgin is symbolized both by the white rose, which indicates virginity, and by the red rose which regards to her charity. Furthermore, in the iconography of Saint Therese of the Child Jesus, the saint is represented with her hands full of roses, a symbol of the graces that she dispensed during her life and after her death. Saint Rita of Cascia has also always been associated with roses; on her deathbed, she asked for a rose from his parents' garden. Although it was winter, a beautiful rose was found on the shrub indicated by the saint.

Detail of the dove

The Rain of Flowers, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 x 98 cm, 2023

The Sun and the White Dove, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 x 98 cm, 2023

Detail of Day

Detail of Night and Sleep

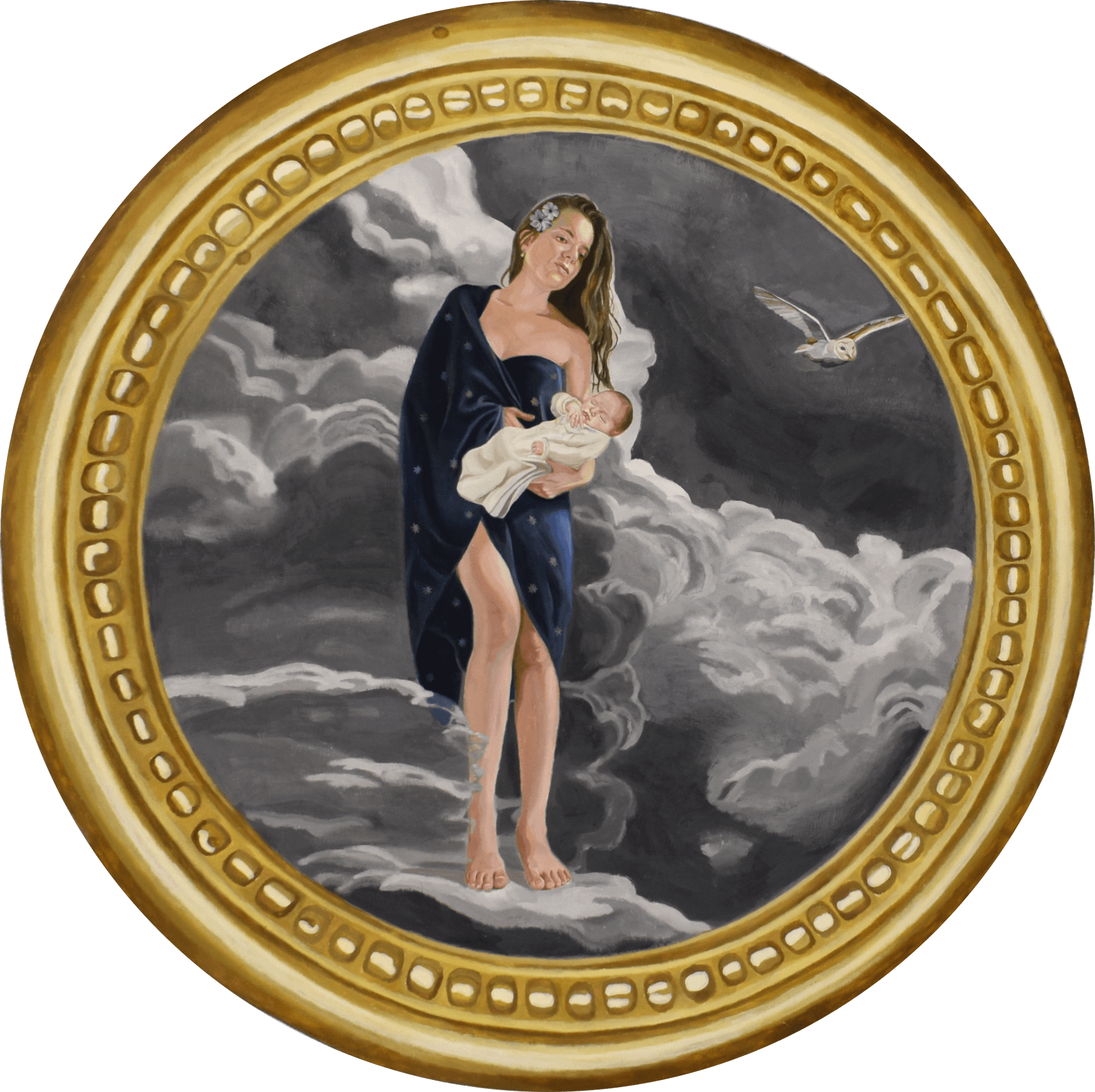

The Night, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 cm, 2023

Otherwise, in the Night roundel, in the second section, at the back of the room and near the window, the personification of Night is represented standing surrounded by dark gray clouds against a background of black sky, wearing a dark blue starry dress and carrying her son Sleep. The hair of the Night is adorned with two flowers known as four o'clock (Mirabilis jalapa). These open at dusk, giving us a beautiful nocturnal show. To the right of Night, above, a barn owl is depicted, which belong to an order of birds of prey with predominantly nocturnal habits. From the ancient world, they are the emblem of a symbolic ambiguity, representing on the one hand wisdom, luck and goodness, and on the other the bearer of dire news and nefarious events. The Middle Ages preserves this double meaning even if Christian art enhances its positive aspect since the animal has the ability to fly above everything, expressing its closeness to Christian holiness, thus representing man's initiatory path of truth and goodness. In ancient tradition it mainly indicates wisdom and philosophy (the "minerva's owl"). Its ability to see in the dark becomes a symbol of wisdom, of clarity of ideas, of rational intelligence that discerns where others only see shadows and darkness. In the Christian tradition, Christ alone, who keeps watching during the night in which he is betrayed, can say with the Psalmist: "I have become like the owl among the ruins, like the solitary bird on the roof" (Ps 102:7).

Finally, in the lateral polygons of the Night roundel, the same nocturnal birds are represented on the right, flying among the gray clouds in the darkness and, on the left, the full and shining moon, symbol of cyclicality, change, mystery, motherhood and fertility. The cyclical nature represented by the moon is a symbol of the passage of time: it manifests the perpetual starting over. The variability of the moon is also found in the alternation of seasons, tides and mood. In the Bible, it is the luminary that God created to be "a source of lesser light to govern the night" (Gen 1:16).

Detail of the owl

The Moon, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 x 98 cm, 2023

The Flying Owls, mural painting, tempera on ceiling, 156 x 98 cm, 2023

The Painting Process

For the execution of the painting on the ceiling of an apartment in Florence, Gabriela used the technique of mural painting with tempera. First, she calculated the distances and marked on the ceiling the two circles, each 156 cm in diameter, and then the lateral polygons, each 156 x 98 cm, in which to paint. Gabriela transferred each composition relating to each geometric space (circles and polygons) onto the ceiling surface using a previously prepared carbon paper. The next day, for each composition, she created a layer of color underpainting, in which she applied large fields of tempera color in the main areas and focused on the smaller ones using smaller brushes. She worked gradually, day by day, adding depth and detail after allowing previous coats of color to partially dry.

References

HESÍODO. Teogonia: A Origem dos Deuses. São Paulo: Editora Iluminuras Ltda., 2020.

BIBLE. Portuguese. Holy Bible. Translation of the originals using the version of the Monks of Maredsous (Belgium) by the Catholic Biblical Center. São Paulo: AVE MARIA, 1982. Claretian Edition.

Emera. In Wikipedia. Available at: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emera.

Nyx. In Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyx.

FAVA, Giovanni. Breve storia filosofica della notte. FRAMMENTI RIVISTA. Available at: https://www.frammentirivista.it/breve-storia-filosofica-della-notte/.

DE VIRGILIO, Giuseppe. La notte e il suo simbolismo biblico. Note di Pastorale Giovanile. Available at: https://www.notedipastoralegiovanile.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7456:la-notte-e-il-suo-simbolismo-biblico&Itemid=1011