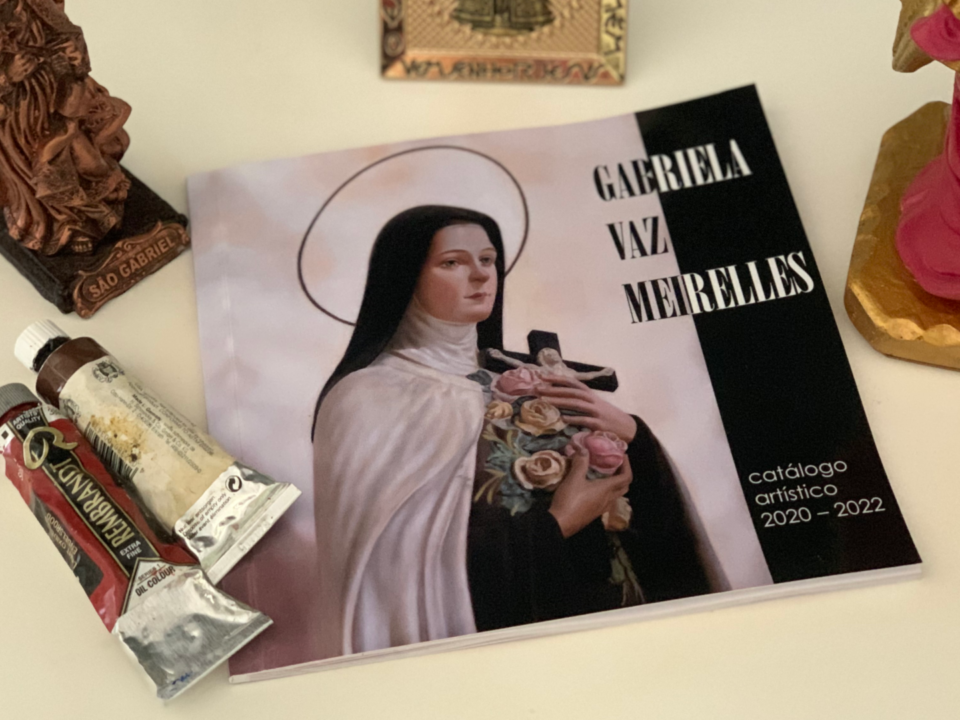

Gabriela Vaz Meirelles, Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus, oil on linen, 80 x 60 cm, 2021

History Background

Thérèse of Lisieux, born Marie-Françoise-Thérèse Martin, known as Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, was a French Carmelite nun known as one of the most influential models of holiness for Catholics and religious alike for her "practical and simple way of approaching the spiritual life".

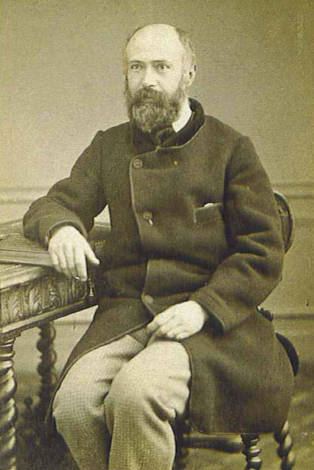

Thérèse was born in Alençon, France, on January 2, 1873, the daughter of Marie-Azélie Guérin, an embroiderer, and Louis Martin, a jeweler and watchmaker, both devoted Catholics, canonized in 2015 by Pope Francis. Louis and Zélie met in early 1858 and were married in the same year in the Basilica of Notre Dame of Alençon.

Determined at first to live the life of brothers, in perpetual abstinence, considering that they had previously tried to dedicate themselves to the consecrated life, they were, however, discouraged by their confessor and ended up having nine children. All five surviving girls later became nuns: Marie, Pauline, Léonie, Céline and Thérèse, the youngest.

Soon after Thérèse's birth in January 1873, there was little hope that she would survive. The enteritis, which had already taken four of her siblings, affected her as well and she had to be placed in the care of a nurse, Rose Taillé, living for some months at her house in the woods in Semallé.

Marie-Azélie Guérin, mother of Thérèse

Louis Martin, father of Thérèse

In April 1874, one Maundy Thursday, Thérèse, only 15 months old and already recovered, returned to her family in Alençon. Throughout her childhood, she was raised in a profoundly Catholic atmosphere, which included daily early Masses, strict observance of fasts, and prayers that followed the rhythm dictated by the liturgical year. The Martins also practiced charity, visiting the sick and the elderly and occasionally entertaining beggars at the dinner table.

On August 28, 1877, Zélie Martin died of breast cancer at just 45 years old. Thérèse was only four and a half years old, but her mother's death had such an impact on her that she would later claim that "the first part of her life ended that day." She remembered the room where Zélie received the extreme unction while she was kneeling at her feet and her father was crying.

Three months after Zélie's death, Louis Martin left Alençon and moved to Lisieux, Normandy, where Zélie's pharmacist brother, Isidore Guérin, lived with his wife and two daughters, Jeanne and Marie. Then he rented a beautiful country house, Les Buissonnets, which was set in a large garden on the side of a hill near the town.

In Lisieux, Pauline took the place of Thérèse's mother and the two became very close. Thérèse also got close to Céline, who was almost the same age. Thérèse was homeschooled until she was eight and a half, when she entered the school run by the Benedictine nuns at the Abbey of Notre Dame du Pré in Lisieux. Partly because of the excellent education she received from Marie and Pauline, she soon became top of her class in all subjects except writing and arithmetic. However, due to her young age and high grades, she was often provoked by her peers, suffering a lot and usually crying in silence.

Rue Saint-Blaise's house at Alençon, Thérèse's birthplace

The house in Semallé where Thérèse lived with Rose Taillé

Les Buissonnets, the Martin family house in Lisieux

When she turned nine, Pauline entered the Carmel of Lisieux and Thérèse was devastated, as she understood that Pauline would move into the cloister and the two would never see each other again. However, the shock led Thérèse to decide to join the Carmelites as well, but she was too young.

At this time, Thérèse was often ill, suffering mainly from nervous tremors. They started one night after her uncle took her for a walk and the two started talking about Zélie. The family called a doctor to try to find out what was going on. In 1882, Dr. Gayral diagnosed that Thérèse "reacted to her frustrations with a neurotic attack". Thérèse finally recovered after she turned to look at the image of the Virgin Mary that sat in Marie's room, where Thérèse had been moved. According to her, on May 13, 1883, the Virgin gave her a smile. However, when Thérèse told the Carmelite nuns about her vision, she felt cornered by their questions and lost her newfound confidence. Doubt made her begin to question her own experience. Thérèse's preoccupation with the incident would continue until November 1887. In October 1886, Marie, her closest older sister, also entered Carmel, adding to Thérèse's torment. Thérèse also suffered from scruples, a psychological condition shared by other saints, such as Alphonsus Liguori and Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits.

Christmas Eve 1886 was a turning point in Thérèse's life, an event she called a "complete conversion". Years later, she claimed that it was that night that she finally got over the pressures she had faced since her mother's death. That night Louis Martin and his daughters Léonie, Céline and Thérèse had attended midnight mass at the cathedral in Lisieux. At home, Thérèse, as was the habit of French children, left an empty shoe on the fireplace waiting for presents, not from Santa Claus, but from Baby Jesus, who, it was believed, would fly in with gifts and cakes. As she climbed the stairs, she heard his father tell Céline: "Well, luckily this will be the last year!". Thérèse started to cry and Céline recommended that she did not come down again at that moment. Then, suddenly, Thérèse recomposed herself, wiped her tears, ran downstairs, and, kneeling by the fireplace, opened her gifts as cheerfully as in past years. In her account, nine years later, in 1895, she told that, in a moment, Jesus, happy with her good will, accomplished what she had not been able to accomplish in ten years.

Before the age of fourteen, already in her period of inner calm, Thérèse began to ardently read "The Imitation of Christ" by Thomas à Kempis, as if the author had written every sentence for her. From then on, Thérèse began to read other books as well, mainly on history and science.

"The Kingdom of God is within you’ (Lc 17,21). Turn thee with thy whole heart unto the Lord; and forsake this wretched world: and thy soul shall find rest."

THOMAS À KEMPIS

Thérèse aged 3 (1876), 8 (1881), 13 (1886) and 15 (1888)

In May 1887, Louis, aged sixty-three, was recovering from a minor stroke when Thérèse went to talk to him. She said she wanted to celebrate the anniversary of her "complete conversion" by joining Carmel before Christmas. They both cried, but Louis got up, picked a small white flower with care to preserve the root, and gave it to his daughter, explaining the care with which God created and preserved her until that day. Thérèse later wrote about the event, saying that as she listened, she believed she was hearing her own story. For Thérèse, the flower was a symbol of herself, "destined to live in another soil".

In November 1887, Louis took Céline and Thérèse on a pilgrimage to Rome for the Jubilee of Pope Leo XIII. The cost of the trip greatly restricted those who could make it. Protected by her youth, she ignored the political events of the time and their motivations, but she did noticed "social ambition and vanity". The stops followed one another incessantly, Milan, Venice, Loreto, until the final arrival in Rome. On November 20, 1887, during a general audience with Pope Leo XIII, Thérèse approached him, knelt and asked permission to enter Carmel at the age of fifteen. The Pope's answer was "Well then, my daughter, do what the superiors decide... You will go in if it is God's will" and blessed Thérèse. She then refused to leave and the Swiss Guard had to carry her out of the room. The journey continued and the group visited the ruins of Pompeii, Naples, Assisi and began the return journey passing through Pisa and Genoa. The nearly month-long pilgrimage came at a good time to help her personality develop. She "learned more than in years of study". Shortly thereafter, the Bishop of Bayeux authorized the prioress to receive Thérèse, and in April 1888 she finally became a Carmelite postulant.

The Lisieux Carmel

Inside the Carmel

The Carmo Order was reformed in the 16th century by Saint Teresa of Ávila and is basically dedicated to personal and collective prayers. Founded in 1838, the Carmel of Lisieux had, in 1888, 26 nuns of all origins and social classes. Thérèse's period as a postulant began with her reception at Carmel on Monday, April 9, 1888, the day of the Feast of the Annunciation. For most of Thérèse 's life, the prioress was Marie de Gonzague. From childhood, Thérèse had dreamed of a "desert" where God would one day lead her and now she was in it.

During her period as a postulant, Thérèse had to face some form of bullying from the other sisters, mainly because of her poor aptitude for manual tasks and crafts. This period ended on January 10, 1889, when she finally took the habit. From then on, she wore the "rough, hand-stitched brown scapular, white cap and veil, leather belt with a rosary, wool socks and rope sandals." Thérèse deepened her sense of vocation: leading a secluded life, praying and offering her suffering to priests, completely forgetting herself, in order to increase her discreet acts of charity. In Thérèse's words, she applied herself especially to the practice of the small virtues, as she was unable to carry out the greatest ones.

Along with the new name that a Carmelite receives when she enters the order, there is always an epithet that underlines the mystery that the nun must contemplate with special devotion. Thérèse had two, and for her they mattered equally. The first, "of the Child Jesus", was promised to her at the age of nine by Mother Marie de Gonzague, and she received it as soon as she entered the convent. The veneration of the Baby Jesus was a Carmelite tradition dating back to the 17th century, focused on the impressive humiliation of divine majesty in assuming an extremely weak and powerless form. However, when Thérèse adopted the habit, she asked Mother Marie to give her a second epithet, "of the Holy Face".

Generally, the novitiate that preceded the profession of faith lasted a year, but it wasn't until September 8, 1890, at the age of seventeen and a half, that Thérèse finally made her profession of faith. Her spiritual life became more and more guided by the Gospels, which she always carried with her. In February 1893, Pauline was elected Prioress of Carmel and became "Mother Agnes". On July 29, 1894, Louis Martin died. Already very ill, he was under the care of Céline, who, encouraged by Thérèse's letters and the advice of the other sisters, also joined the Carmel in September. Along with her camera, Céline also took notebooks with passages from the Old Testament and Thérèse found one from the Book of Proverbs that had a great impact on her. She was also very impressed with a passage from Isaiah, and concluded that Jesus would take her to the heights of holiness. Thérèse's smallness and her limitations became reasons for joy rather than discouragement. It was only in "Manuscript C" of her autobiography that she named her discovery "little way". This "little way" of Thérèse is the foundation of her spirituality.

"Whosoever is a little one, let him come to me."

PROVERBS, 9:4

Thérèse's final years were marked by a rapid decline in her health which she endured resolutely and without ever complaining. She had tuberculosis, but she saw the disease as part of her spiritual journey. In her final hours, Thérèse exclaimed that she would never believe it was possible to suffer so much! Saint Thérèse died on September 30, 1897 at just 24 years old. She was buried on October 4 in the Carmelite space in the municipal cemetery in Lisieux along with Zélie and Louis Martin, her parents. On her deathbed, her last words were "My God, I love you!".

Thérèse in her first years at the Carmel

Thérèse in her final years at the Carmel

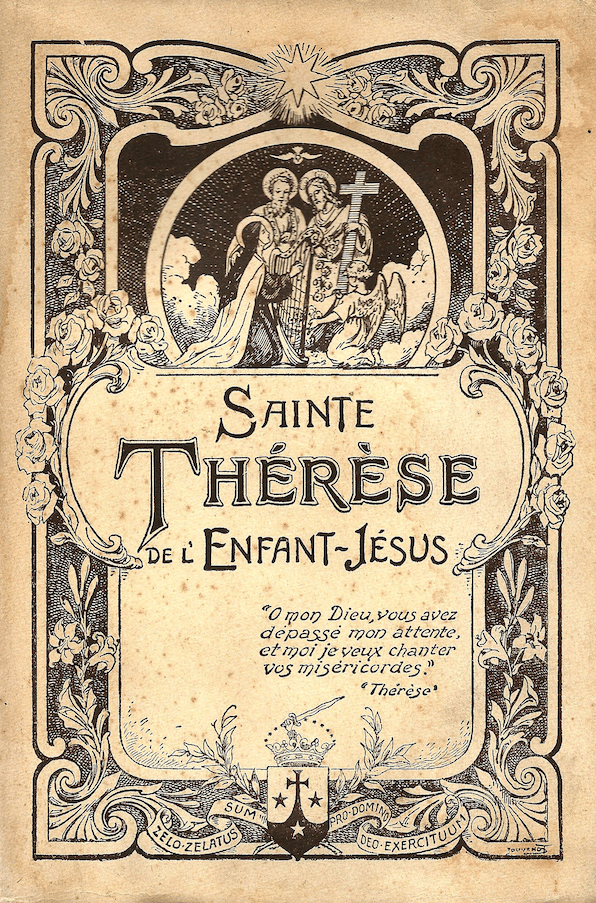

The Story of a Soul

Saint Thérèse is still very popular today because of her spiritual memories, described in the book "The Story of a Soul" (L'histoire d'une âme). She began writing it in 1895 as a memoir of her childhood. While Thérèse was in her retreat in September 1896, she wrote a letter to Marie which is currently part of the edition of "The Story of a Soul". In June of the following year, Agnes learned of the gravity of Thérèse's situation and immediately asked Mother Marie de Gonzague to allow Teresa to write another memoir, this time focusing on the details of her religious life. Including a selection of Thérèse's letters, poems, and recollections of her reported by the other nuns, the work was published posthumously. The text was heavily edited by Mother Agnes, who presented it as an autobiography of her sister.

After the success of the book, which sold over 500 million copies, popular devotion to Thérèse of Lisieux grew rapidly in France and around the world, being accompanied by testimonies of conversions and physical healings. Since the end of the 19th century, people have prayed to the “little saint” long before the Church canonized her.

Cover page of "The Story of a Soul" by Thérèse, 1940

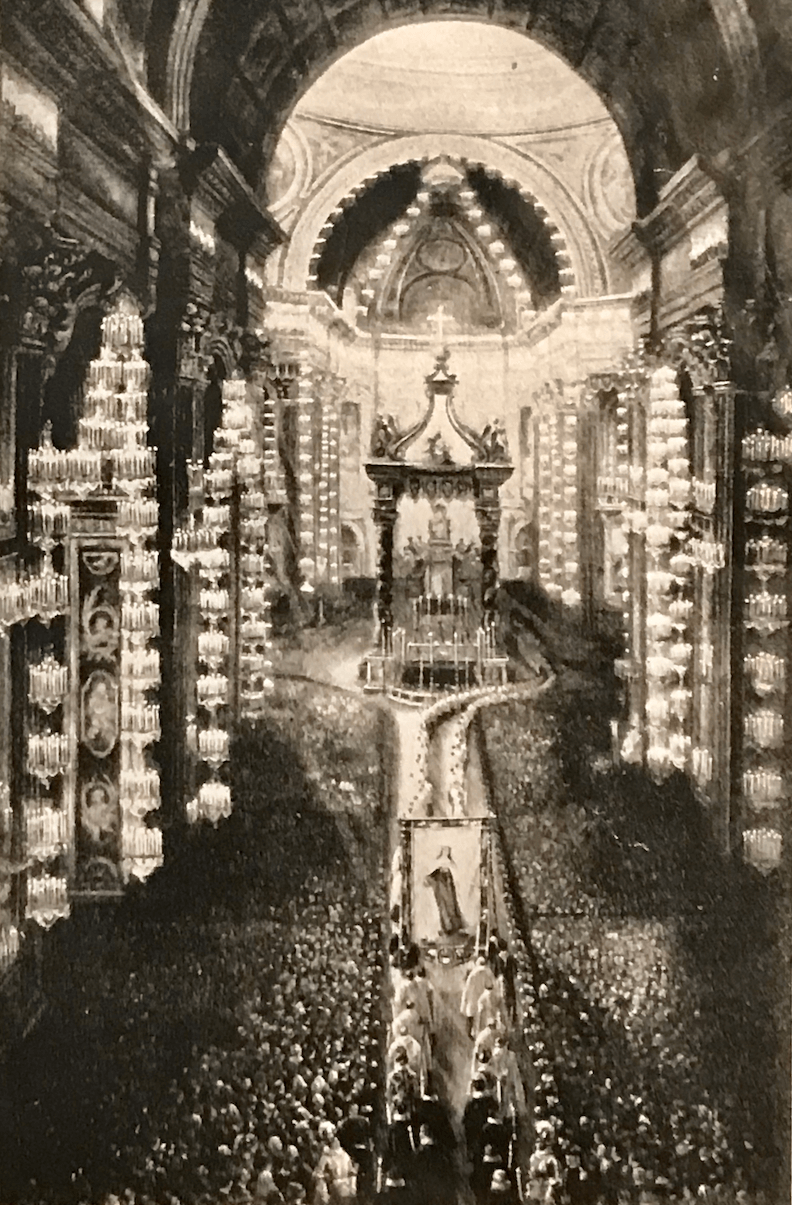

Saint Thérèse's canonization on May 17, 1925

Pope Pius X signed the decree authorizing the opening of Thérèse's canonization process in 1914. Pope Benedict XV, to speed it up, dispensed the usual fifty years required between death and beatification. Thérèse was beatified on April 29, 1923 and canonized on May 17, 1925 by Pope Pius XI, just 28 years after her death. Her feast was included in the General Roman Calendar in 1927 on the 3rd of October. In 1969, Pope Paul VI moved the feast to October 1, the day of her heavenly birth. Through the 1997 apostolic letter "The Science of Divine Love", St. John Paul II proclaimed Thérèse a Doctor of the Church, one of four women to have received the honor so far (the others were St. Thérèse of Avila, St. Catherine of Siena and St. Hildegard of Bingen).

Along with St. Francis of Assisi, St. Thérèse is one of the most popular Catholic saints since the apostolic era. As a Doctor of the Church, she is subject to intense theological debate and study, and as a young woman whose message touched the lives of millions, she is the focus of fervent popular devotion. In fact, charity is measured not by the quantity of works or by their greatness, but by the intensity of the love with which they are done.

"Nothing is small when love is big."

THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX

An Inspiration From Rimini

To portray Saint Thérèse, Gabriela did not base herself on one of Thérèse's photos from the time, but on a statue that, among many others, caught her attention during her last trip to Rimini, Italy, in 2020, located at the Church of Saint Agostino. This was due to the beauty of the form and simplicity of her gaze, sweet and sincere, just as the artist imagine the saint's should have been. Gabriela did the painting in oil on a fine linen canvas measuring 80 x 60 cm, which was donated to Father Luiz Augusto from the Parish Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus (Paróquia Santa Teresinha do Menino Jesus), in Aparecida de Goiânia, Brazil, for his beautiful and blessed work.

Church of Saint Agostino in Rimini, Italy

Parish Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus in Aparecida de Goiânia, Brazil

The Painting Process

Gabriela developed the painting of Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus following the Old Masters technique. After stretching the fine prepared oil linen canvas, she applied a cold medium gray color to the entire surface with a palette knife. For the underdrawing layer, Gabriela transferred the composition to the surface of the primed linen using a burnt umber color. In the next day, she did a warm grisaille layer using a mixture of transparent oxide brown and raw umber. She then applied successive dead layers of a mixture of white and raw umber to adjust the form and tone of the saint's face and hands. For the color underpainting layer, she applied broad fields of color in the major areas and turned to the smaller ones using smaller brushes. She worked gradually, day after day, returning to most areas several times to add depth and details after allowing previous coats of color to partially dry. Finally, she did the glazing stage using very thin layers of transparent colors and let the painting dry. After it was completely dried, she applied a thin layer of varnish to protect it from dirt and dust, to revive the colors and even out the painting's final appearance.

Development of Gabriela’s Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus

References

TERESINHA, S. História de uma alma: manuscritos autobiográficos (tradução das Religiosas do Carmelo do Imaculado Coração de Maria e de Santa Teresinha). São Paulo: Paulus, 1986.

Thérèse de Lisieux. In Wikipedia. Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Th%C3%A9r%C3%A8se_de_Lisieux

MIRACLE of Saint Thérèse. Directed by Andre Haguet. France: Paris Studios Cinema, 1952. 1 DVD (90 min.).

THÉRÈSE. Directed by Leonardo Defilippis. USA: Saint Luke Productions, 2004. 1 DVD (96 min.).